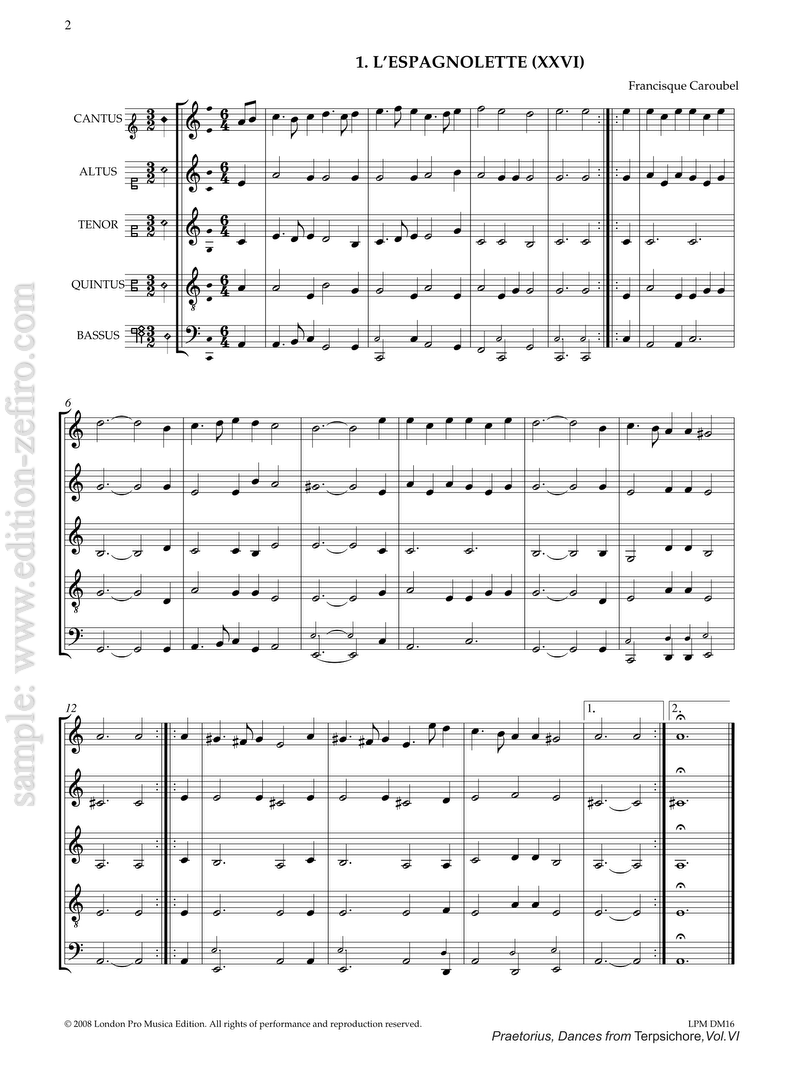

This volume contains some of the longer, more elaborate five-part settings, including some ballet suites.

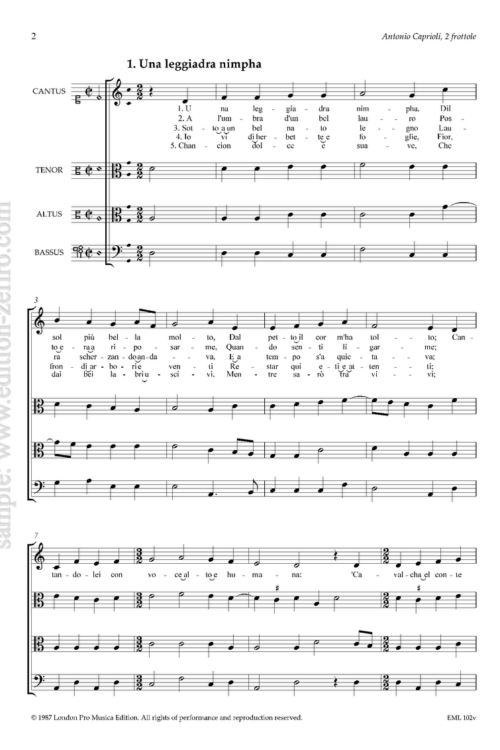

Score and parts.

The other volumes in this Terpsichore collection.

- Dances… Volume 1 ↣

- Dances… Volume 2 ↣

- Dances… Volume 3 ↣

- Dances… Volume 4 ↣

- Dances… Volume 5 ↣

- Dances… Volume 6

Extract from the editors introduction to the volumes 1 to 6

Praetorius makes it fairly clear in his introduction that the melodies of the dances in Terpsichore were originally composed by various French violinists and dancing-masters, and that most of them were supplied by Anthoine Emerald, a dancing-master working in Brunswick. Several of the pieces have the name of a musician in their title, such as Wustrow or de la Moth.

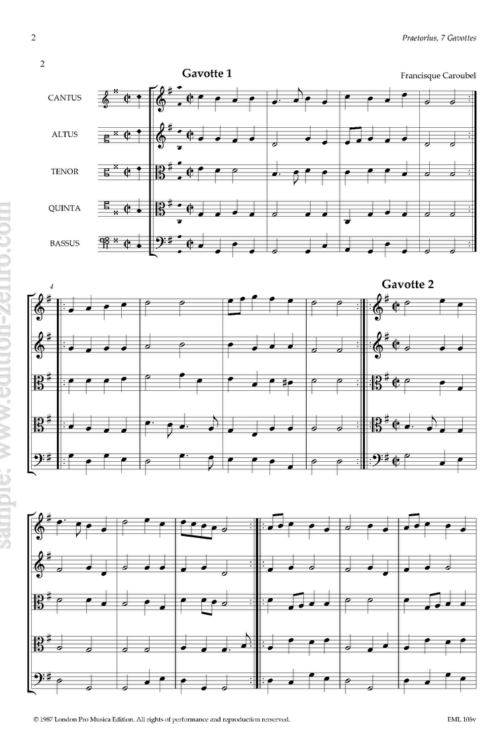

In most cases Praetorius had only the melody to go on, and simply added the remaining parts, but there is a small group of pieces labelled ‘incerti’ in the original, where Praetorius was also provided with a bass part, so only had to fill in the inner parts, a considerably easier task. However, there is also an important group of about 70 dances attributed to Francisque Caroubel, another French violinist who happened to visit Wolfenbüttel in 1610; here it seems that Caroubel was responsible for all the parts, though again in many cases the tunes would probably have been composed by other musicians.

Not all the tunes in Terpsichore are French in origin. There are settings of English ballad tunes such as Wolsey’s Wilde, Light of Love, Packington’s Pound and the tune set by Dowland as Mistresse Winter’s Jump. Other English pieces include the Bataille Coranto of John Bull, and there is a setting of the Dutch song, Willem van Nassau. The English dance tunes may have come to Praetorius’ attention via some of the English violinists working in North Germany at the time (e.g. William Brade and Thomas Simpson), but not necessarily so. Dance music has a habit of travelling long distances, and this was almost as true in the Renaissance as it is today. So we should not be surprised to find a courante apparently based on Vecchis’s So ben mi ch’ ha bon tempo. And there is a group of classic Spanish dances of the kind that ended up as standard Italian repertoire, the Spagnoletta, Pavaniglia (Pavane de Spaigne) and the Canarios. A good example of a dance that was widely known in Europe is the Branle de la Torche, which has survived in settings by D’Estrées and Zanetti, and a keyboard arrangement by Antonio Valente, and for which Arbeau gives a choreography.