Jacob van Eyck was known in his lifetime as an expect on church bells.

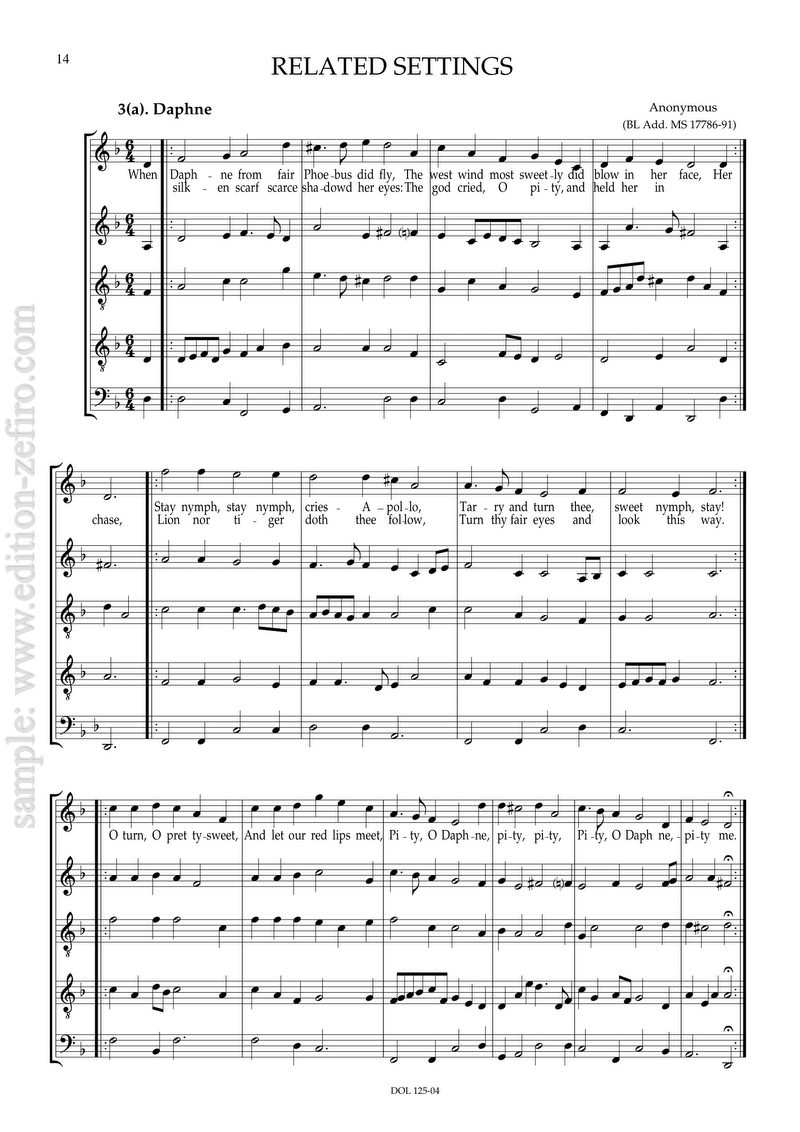

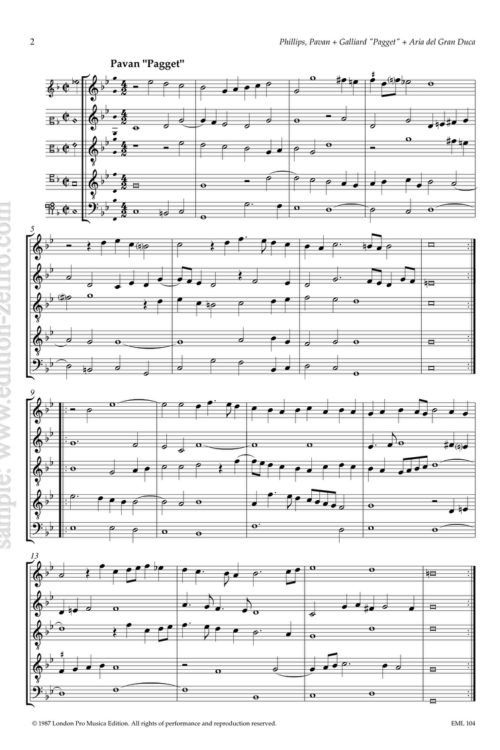

But he also published this book of solo music for recorder.

Apparently he would entertain congregations at his church in Utrecht by playing these instruments.

The collection was dedicated to Constantijn Huygens, a distinguished figure in Dutch political life, and also a keen amateur musician. It is unlikely that Mr Huygens was unduly impressed by FLH, as he is on record as preferring the conventional instruments of the aristocracy (lute and viol), and also disapproving of sets of variations, which he thought were too prevalent in Holland. However, as he was a distant relative of van Eyck, he presumably had to make nice, or risk a family rift. For more than twenty years FLH has been available in a nice facsimile published by Saul B. Groen in Amsterdam. It is also the subject of an excellent and thorough study by Ruth van Baak Griffioen

The original title page to FLH does not specify instruments, but the introduction includes illustrations of two instruments. The first is a little recorder nominally in C, with a range of two octaves and a tone (see our front cover), for which the composer gives a fingering system. No instrument corresponding exactly to that illustrated by van Eyck has survived, though similar instruments are frequently illustrated in Dutch paintings of the period. The second is a little alto flute in G, which shares the top note of the recorder, but descends an extra fourth. Unfortunately van Eyck (or his publisher) did not provide fingerings for this, but promised more information in a proposed third volume.

Jacob van Eyck (1590-1657), who was born blind, was by trade mainly a carilloneur at Utrecht, where he was a renowned expert on the acoustics of bells: he was in fact responsible for improving the bells in several buildings in that city. But as we know now he was also a keen recorder player, and in the 1640s one of his duties was to play this instrument in the gardens of the St. Janskerk on Sunday evenings, so in a sense the Lusthof (or pleasure-garden) in the title is only partly metaphorical (though such titles were very common at this time an earlier example is Hassler’s Lustgarten of 1601).

(The three paragraphs above are taken from the introduction by Marijke Oostenkamp and Bernard Thomas)