A complete edition of Antico’s remarkable collection which consists entirely of double and even triple canons.

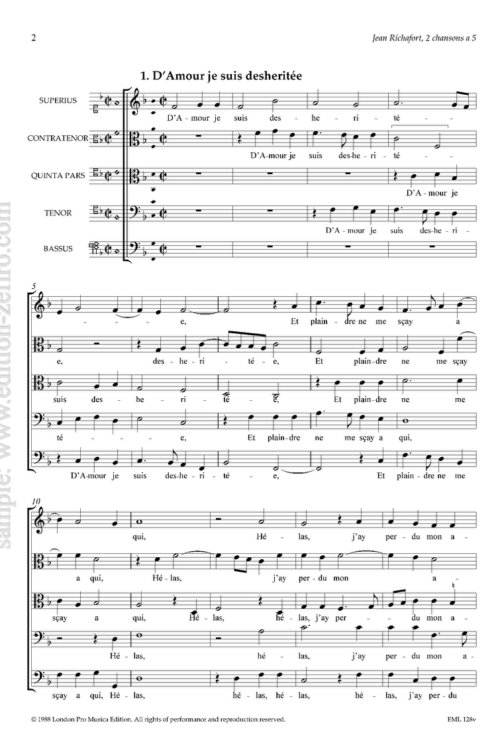

In 1520 the Venetian publisher Andrea Antico issued his Motetti novi e chanzoni franciose a quatro sopra doi. The title is a little misleading, as not all the pieces are double canons. No. 1 is a quadruple canon from a single part, no. 9 has 4 parts derived from a single part,together with a“free” fifth part,no.10 is a triple canon (i.e.with three canonic pairs), while no.11 has four canonic pairs. No. 21 is barely a canon at all: it seems to require the note G in the two inner parts to be alternated in different octaves, though other interpreations may be possible.

The texts of the motets tend to be Marian, which fits in with the practice of the day: texts devoted to the Virgin Mary were often treated as experiments in texture,as in Josquin’s classic 4-part Alma Redemptoris Mater (printed in LPM 562),in which the parts lie very close together.

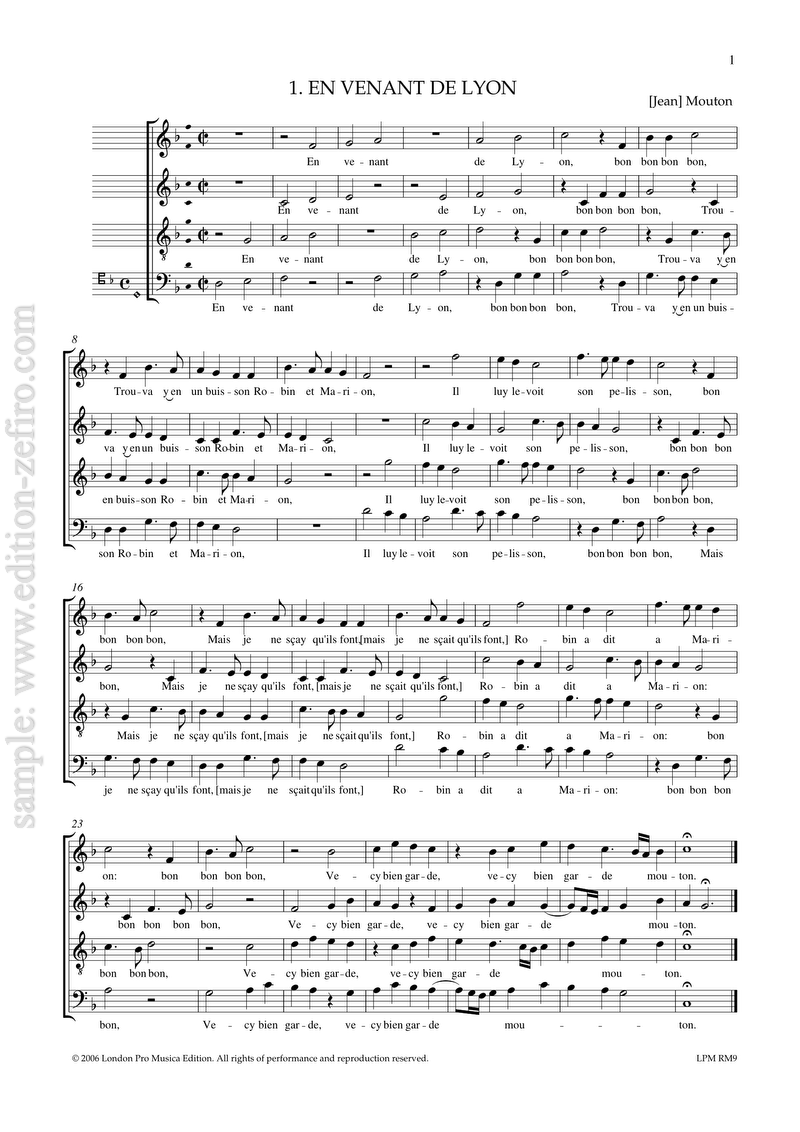

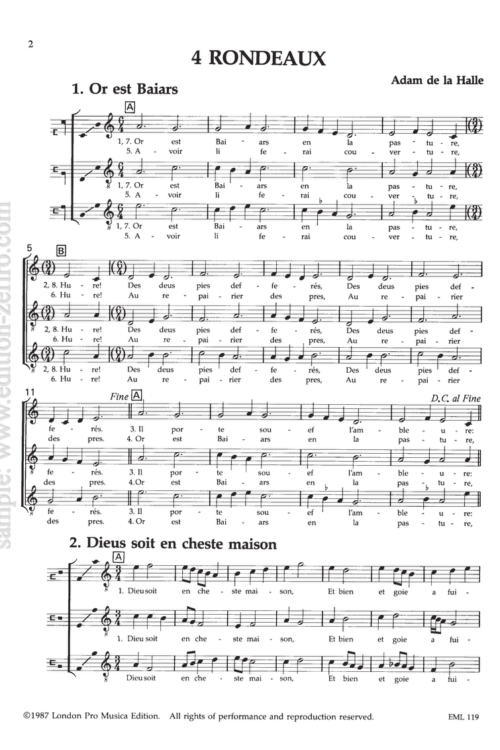

The secular pieces are essentially chansons rustiques, that is pieces either based on popular melodies that had crept into art music towards the end of the fifteenth century, or newly composed pieces using chanson rustique texts; it is possible to happily waste large amounts of time arguing about which is which. An exception is Mouton’s short but touching elegy for the composer Antoine de Févin (no.18), though even here the language of the poem has the simplicity of a chansons rustique.

Adrian Willaert contributed the largest number of pieces to the collection, with eight in all. Although there are only a couple of (non-attributed) pieces by Josquin des Prés, the spirit of this composer seems to pervade the collection. Josquin was the master of effortless canon,and most of the composers in Antico’s collection were heavily influenced by him. One piece, Jean Mouton’s Adieu mes amours is directly based on a work by the older master: Josquin’s setting has a pair of parts in fairly strict imitation, and it as if Mouton decided to try one better than his teacher by producing a double canon on the same tune – it is one of the most successful pieces in the collection.

The most common kind of piece in the collection is the double canon at the fourth. Such pieces raise the question as to whether the imitation should be absolutely exact, so that the imitating parts are in a key a degree sharper than the opening parts. It seems that is some cases this is intended, but in other pieces, such as no. 26 applying this principle produces the most impossible musica ficta problems. It would seem that a prag- matic approach to this question is required. It would of course be quite in the spirit of the Renaissance approach to performance for musicians to make their own decisions about such things. Several pieces where we have chosen the bi-tonal option, as it were, with raised leading notes on two different pitches, could be modified so that only one part has the leading note, and the sixth note of the scale (e.g. E in transposed Dorian starting on G) should be lowered where possible, especially in the bass part at cadences.

Two of these canons at the fourth are written so that the imitating parts can begin at two different points. Both are settings of Mon petit cueur, and indeed they would seem to be related,suggesting a certain (friendly?) rivalry between two composers.

As well as the many canons at the fourth (or fifth, not essen- tially any different),there are canons at the octave, and at more unusual intervals, such as the third (no. 3), the sixth (23), the

seventh (no. 5) and the tenth (no. 2). Usually the interval is made clear, (“ad diatessaron, ad tertiam”, etc.) but occasionally the instructions are more cryptic, as in no. 5, in which we are told: “Quilibet manebit in sua vocatione”, but the interval of a 7th is in fact indicated by the two sets of clefs.

EDITORIAL NOTE

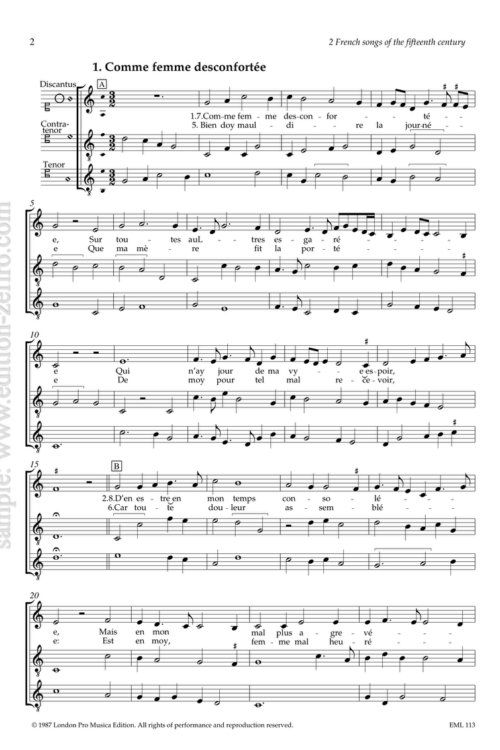

In this edition the original note values have been halved, except in no. 13, in which they have been quartered. Original accidentals, printed on the stave, are taken as applying to the whole bar unless corrected, for the sake of simplicity. Purely editorial accidentals are printed small above the stave, applying to the one note only. I am grateful to Nigel Coulton for translating the Latin texts. The translations of the French texts are by Alan Robson and Jean-Pierre La Fage.