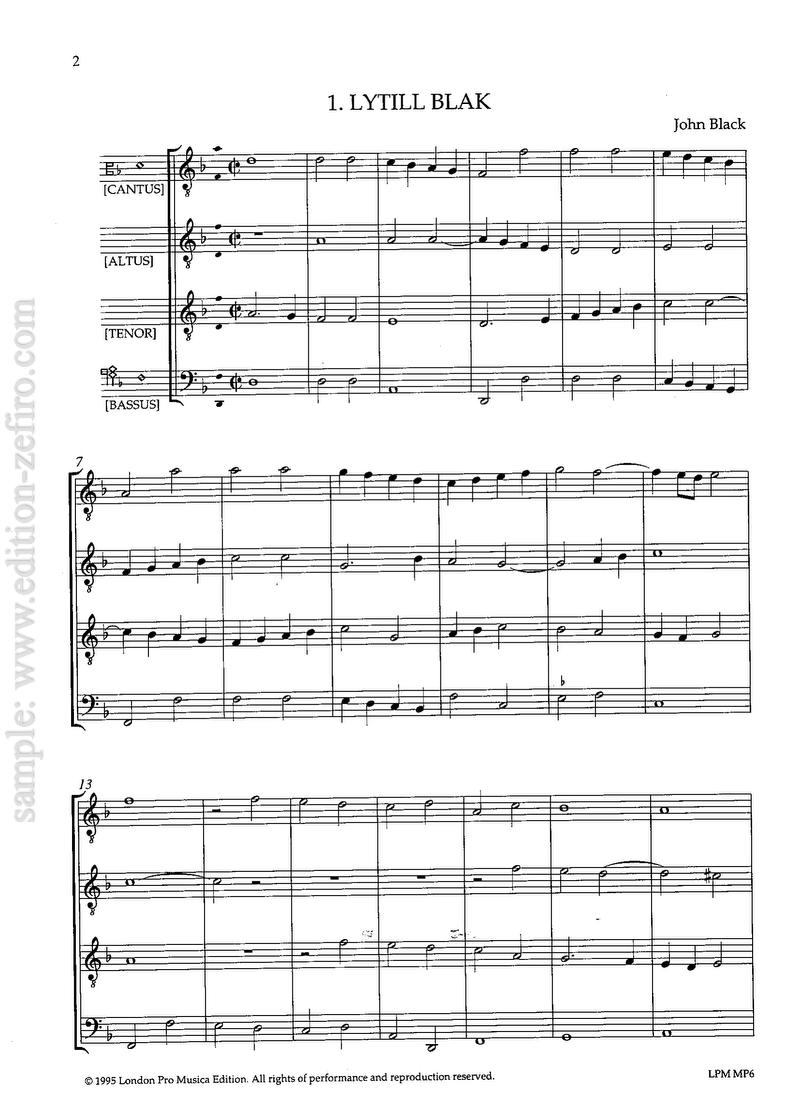

This is a collection put together by Charles Foster than includes songs and dances by John Black and others.

Although music in Scotland flourished during much of the 16th century in its Royal Court and in its Churches with their associated “Sang Schules”, only a very small quantity of music has survived from that period. This is particularly so in the case of secular part-music; fewer than three dozen songs, a handful of nutrimental fantasies, and around half a dozen dances are all that now remain from a once rich heritage. The blame for this can be cast quite squarely on the influence of the Reformed Church, which forbade the printing of any secular music. It was not until 1662 that the first book of secular music made its appearance, namely the Cantus, Songs and Fancies published by John Forbes in Aberdeen.

The Reformed Church regarded all secular songs, particularly those in parts, as “prophaine sangs”; these were proper only if new moralised texts were substituted, for “avoiding of sinne and harlotrie“.

On one occasion a psalm was even decried for being “in filthie pairts”. Certain of these new texts are so vitriolic in their vituperation of the Catholic Church as to make the most bigoted 20th century Protestant preacher in Northern Ireland seem in comparison quite ecumenical.

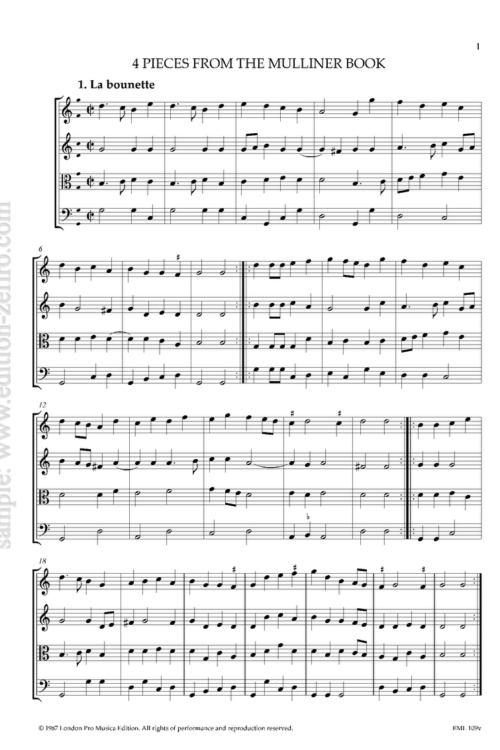

Strictures against dancing were even more severe. John Knox, the most influential and vociferous Protestant reformer, is recorded as having devoted entire sermons to inveighing against the immorality of dancing, in particular that in which the reigning monarch, Mary Queen of Scots, indulged. This severity continued well into the 17th century with the forbidding of “idle pyping or promuscuous dancing“. The variety of dances in which the Scots engaged before the Reformation is made clear in The Complaynt of Scotland, (1549).

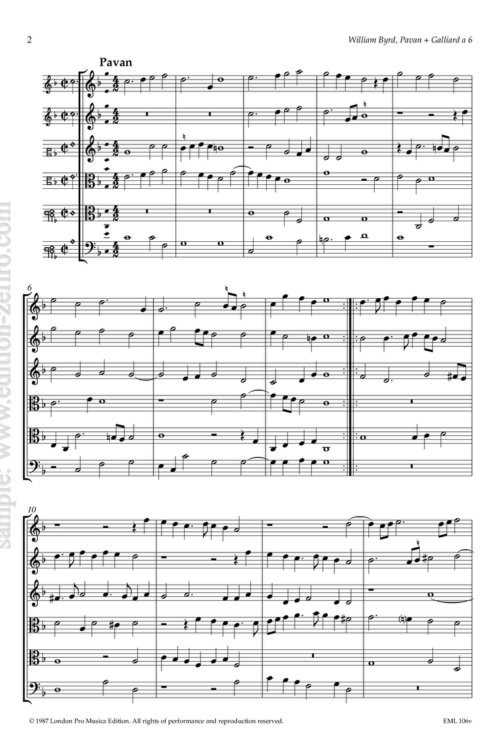

This work at one point describes shepherds “dans and base dansis, pavvans, galyardis, tirdions, braulis, and branglis, buffons vitht mony uthir lycht dancis the whilk ar ouer prolixt to be rehersit.” Here the author enumerates the most important dances, all of which are well known in continental sources; “braulis” and “branglis” are most likely one and the same, namely “bransles”. He continues by saying there are many more dances, too numerous to recall, and then goes on to do precisely that, with a long list of mainly regional dances – “yet nochtheles i sal rehers sa many as my ingyne can put in memorie; in the fyrst thai dancit al cristyn mennis dance, the northt of scotland, huntis up, the comment entray, lang plat fute of gariau, Robene hude, thom of lyn, freris al, ennyrnes, the loch of slene, he gosseps dance, levis green, makky, the speyde, the flail, the lammes vynde, sutra, cum kyttil me naykyt vauntounly, shayke leg, fut befor gossep, Rank at the rute, baglap and al, ionne ermistrangis dance, the alman haye, the bace of voragon, dangeir, the beye, the dede dance, the dance of kylrynne, the vod and the val, schaik a trot.” The very titles of certain of these are capable of causing offence, for example, “cum kyttil me naykyt vantounly” can literally be rendered “come tickle me naked wantonly”!

Several of these and other similar pieces have survived in versions for lute, pandora, cittern and virginals in 17th century manuscripts, but the handful of dances composed in parts which has survived consists entirely of “pavens” and “galyiardis”.