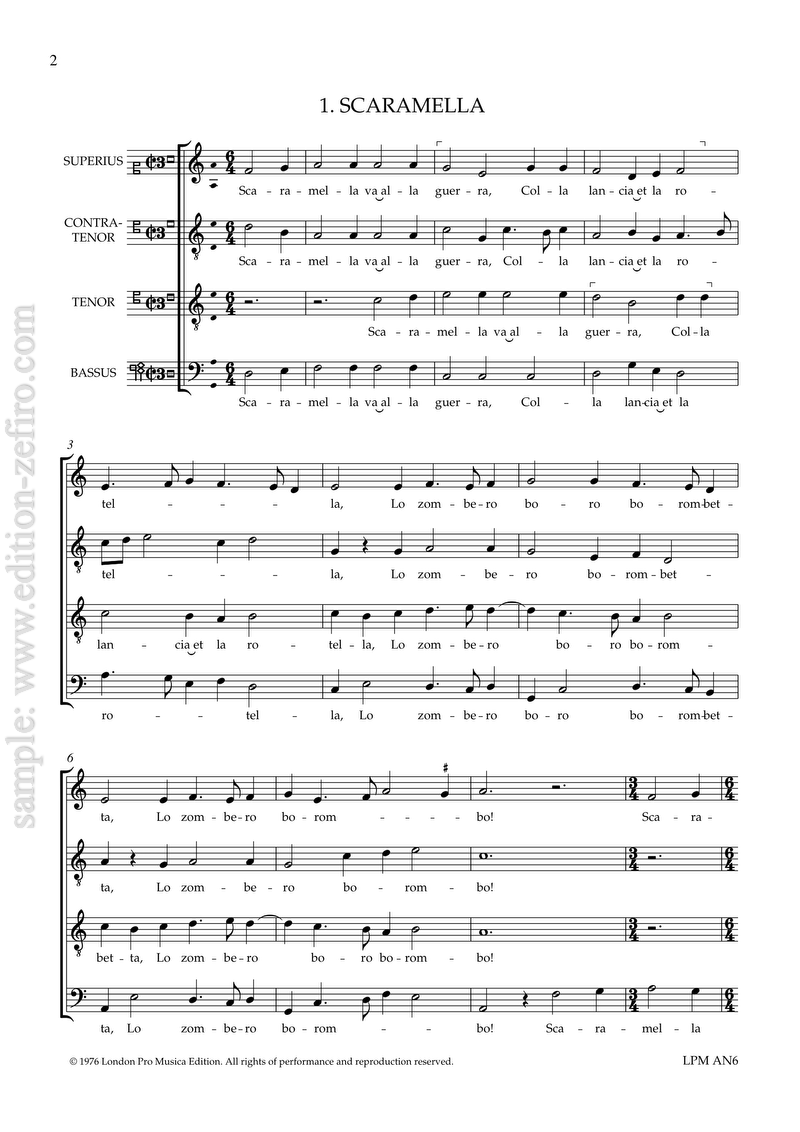

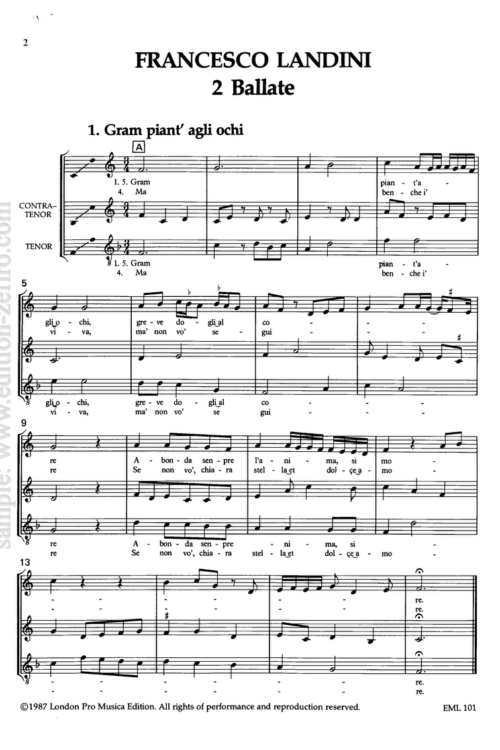

A little volume that explores the lighter side of this central figure of Renaissance music.

Suitable for recorders, viols, and several other types of instruments and of course voices. (Score only)

The last two decades of the fifteenth century were probably the most musically exciting years of the Renaissance, It was during this time that the main features of Renaissance style were evolved, and all the important techniques refined. And although a large number of highly gifted composers, including Alexander Agricola, Jacob Obrecht, Pierre de la Rue, Loyset Compère and Antoine Brumel, were all born in the 1440s and 50s, reaching their peak towards the end of the century, it was Josquin des Prés (c. 1440-1521) who contributed more than any other musician to the subsequent development of Renaissance music. Whereas the other men seem to have been largely forgotten after their deaths, Josquin’s works went on appearing in print right through the sixteenth century: the Flemish Publisher Tielman Susato, for instance, found it worthwhile to re-issue a whole book of Josquin’s chansons as late as 1545.

One of Josquin’s main achievements was to concentrate the sometimes over-facile and ornate writing of many of his contemporaries into a taut economical style in which every note seems indispensable. For instance, although his music does use (sparingly) the various asymmetrical rhythmic clichés that so delighted the musicians of his time, he rarely depends on them to keep a piece moving: the long sequences (usually based on units of three or five notes, and often presented in parallel tenths between the outer parts) that pad out the music of Obrecht or Isaac, are strikingly absent in his music. In his search for a real structure in Josquin’s work (as opposed to essentially decorative devices like sequences) Josquin developed the art of imitation in all parts to a much more refined level than any other musician of his time: linked with this was the evolution of a balanced texture in which all the voices are more or less equal. He was very fond of canons, but used them in a remarkably unobtrusive way, more as a means of focusing his integrated textures rather than as a self-conscious intellectual device: there are, for instance, several little double canons that are effortlessly written round popular melodies – Baisés moy is one such (for other pieces of this type see 7 Double Canons ↣ ).

Many of Josquin’s chansons, especially those in four parts, seem to be based on popular tunes of his day: this is probably true of at least five of the seven numbers, in this selection (nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 7). It may seem strange that the most skilled and versatile composer of his generations should have bothered with such simple material. But the influence of popular song played a vital part in the musical revolution that took place at the end of the fifteenth century, led by Josquin himself. It seems that the musicians of this time, who would have been brought up with the long ornate lines of Ockeghem and much of Busnois, felt an urgent need for the direct simplicity of a truly vernacular style of music: the simple songs that these skilled composers used gave their pieces a focus and sense of direction that is extremely refreshing after a diet of pure court music. Actually, the way Josquin used his “borrowed” melodies was rather different from that of his contemporaries. What marks off his pieces from most other popular song settings of the time is the way the melody in each is integrated into the texture: in most of Josquin’s chanson settings motives from the tune are used in imitation in all parts, as in Qui belles amours a. What makes it possible to say that the five pieces mentioned are probably settings of popular tunes of the time is the fact that other settings have survived of these particular melodies. In the case of Belle, pour l’amour de vous, no other settings survive, yet there is no great difference stylistically between this song and Qui belles amours a. So it is quite possible that this piece also is based on a popular melody: the fairly basic language of the verse would tend towards the same conclusion.

Vive le roy was, until recently, assumed to be an instrumental fanfare. But there is really no evidence for this assumption. First of all, court trumpeters at this time had a musical life that was quite separate from that of “art” musicians: it is highly unlikely that they could read music.The only combination of brass instruments on which this piece could be performed would be a slide trumpet and three sackbuts, a grouping that is not supported by any iconographical evidence. The main reason that the piece has been thought to be instrumental is that there are no words in the single source, but as this is an Italian printed collection that does not give any texts (in spite of the fact that most of the music can be shown to be vocal) the argument has no force. Vive le roy has been successfully performed as a vocal piece (by Musica Reservata of London: credit must be given to the director of that ensemble, Michael Morrow, for uncovering the possibility that this might be a vocal number): the simplest possible line of words,“Vive le roy, le bon roy”, fits all the parts very easily. It seems fairly likely that the piece was written for Louis XII of France.