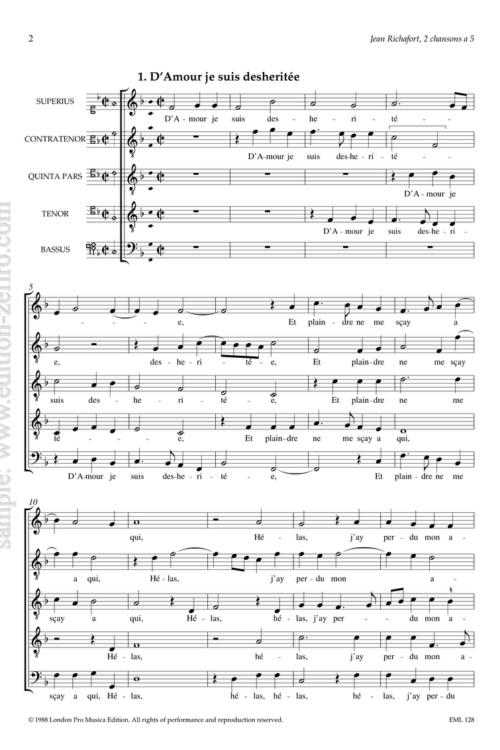

These chansons are from Livre de chansons nouvellement composé a troys parties par Jo. Castro, which was published in Paris by Adrian le Roy and Robert Ballard in 1575.

Little is known about the life of Jean Castro, which is slightly surprising, given the comparatively large amount of his music that was published during his lifetime. He was born around 1540 in Evreux (northern France), and it is likely that he spent the first part of his career at Antwerp, where his earliest publications appeared in 1569 (Il primo libro di madrigali, canzoni & motetti a tre voci). Because of political upheavals in the Netherlands, he moved away to North Germany, where he worked at several of the courts in the area, including Düsseldorf and Cologne; he appears also to have had a spell at Lyons. The date of his death is not known, though his last publication appeared in 1611.

Castro’s surviving output is somewhat unusual, in that most of it is secular, and much of it is in three parts. He also showed a taste for setting verse of some substance: in 1576 he produced a collection of Ronsard settings, and he published many settings of sonnets. Many of his 3-part chansons and madrigals are based on well-known pieces: for instance, he composed skilful arrangements of Rore madrigals such as Ancor che col partire, which play rather attractively with their models.

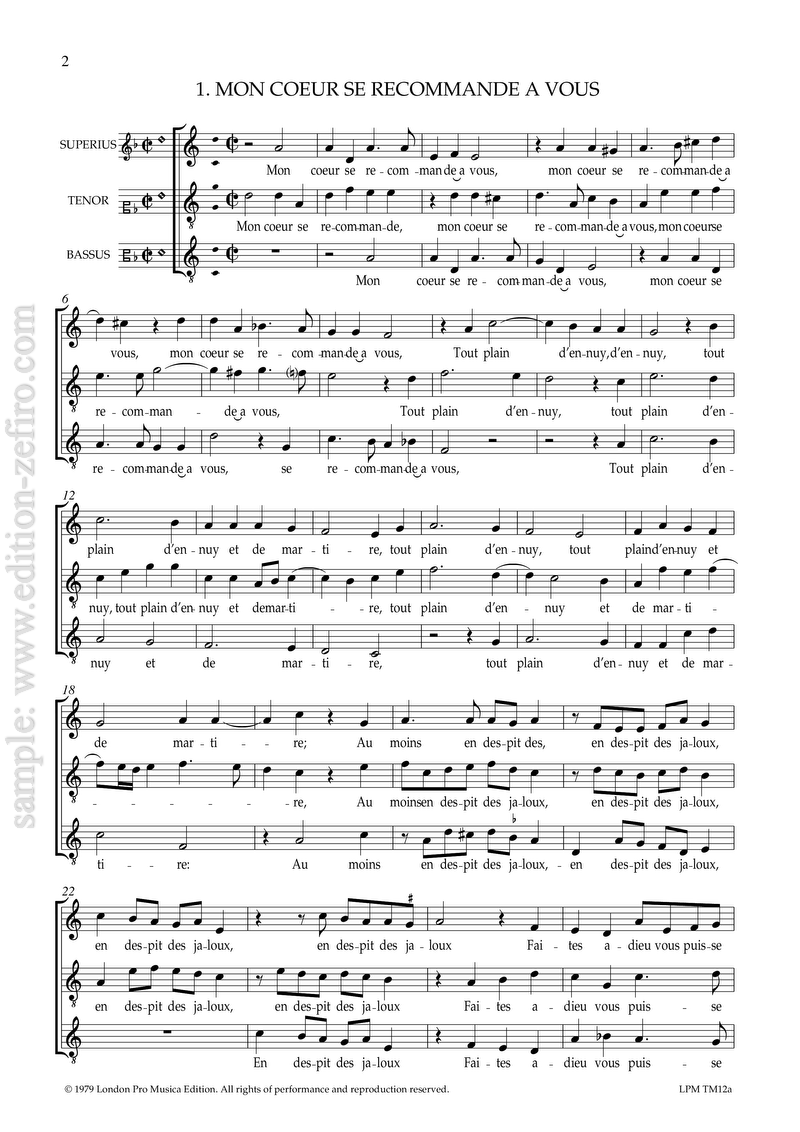

About 20 pieces in the 1575 Livre de chansons, including those printed here, turn out to be (extremely free) parodies of chansons by Lassus; other composers used by Castro for this purpose include Clemens non Papa, Thomas Crecquillon and Adrian Willaert. Castro’s parody treatment is quite interesting. In no case does he simply arrange his 4 or 5-part model in three parts, as his contemporary Gerard de Turnhout did in his versions of the same pieces (see vol. 27 in this TM series). Typically Castro takes one or two motives from his model, and alters the intervals to create lines that remind one of the “original”, but which really work quite differently. The extent to which he refers to the model varies very much from piece to piece: in Bon jour, mon coeur it is only the first phrase in the bass part that appears intact; in this case, as in many others, Castro’s version is more varied rhythmically than its model. A curious, and rather attractive feature is the use of unexpected endings to phrases, such as rising a third to a final weak syllable, or finishing on a resolved suspension without actually making a normal cadence, as in Mon coeur se recommande a vous.

(Bernard Thomas 1979)